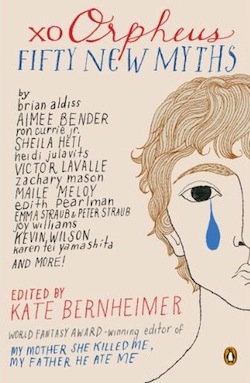

Tor.com is pleased to reprint “Drona’s Death,” a new story by Campbell-nominated author Max Gladstone, writer of Three Parts Dead and the upcoming Two Serprents Rise. “Drona’s Death” is part of the upcoming anthology xo Orpheus, available from Penguin September 26.

War rages on, and Drona is its heart.

Some songs tell of good wars, kind wars, wars where, when the fighting’s over, you sit alone in the woods and breathe and think, this was good, this thing I’ve done. I have saved lives, I have served my king, I am the man I always hoped to be. Drona’s heard these songs; he’s never seen the wars they mean.

This war has lasted fifteen days. Not long, but vicious. Mountains lie broken to shards by warriors’ wrath. No war has been this great since the first one, which gods and demons fought in mortal guise. Cleaner, Drona thinks as he draws his bow. Safer. Gods and demons, each knows the other an enemy. This is war between men, between brothers.

The sun stands one fist’s distance above the eastern horizon. Cries of dead and dying men and elephants, screams of horses and of tortured metal, fill the heavy air. Fifteen days ago there was a jungle here. Now patches of forest stand like tombstones on a blasted heath. There is no word for the world the war has made.

The sun is one fist’s distance above the eastern horizon, and already Drona has killed ten thousand men. He looses an arrow, and a mountain fortress breaks like glass. He feels the men there die. Ten thousand fifty seven.

Two miles away a Pandava chariot swoops low over one of the many wings of the army Drona leads. In the chariot’s wake fire spreads, burning men and fortifications that belong to Drona’s King. Skin flakes and crisps and peels from flesh. Men stagger under that fire as under a weight. A boy runs from the carnage and flame, swift, bearing bow and arrows with him. Brave. No deserter.

Drona looks on the chariot, and sees his student, Arjuna, standing behind the driver. Hair dark as a night without moon, eyes flashing golden and white with the lightning caged inside his body. Arjuna laughs, and Drona remembers the way he laughed as a boy, remembers the day Drona taught him to kneel, to draw sight on a flying eagle, to loose and fix the bird through its eye.

Drona knows he should loose his arrow and kill Arjuna. This is a war between brothers, and brothers die in war.

The stumbling boy turns, nocks arrow, draws and aims at Arjuna’s chariot overhead. But Drona did not train fools, or blind men.

Arjuna has seen the boy. Smooth as poured water, he draws his bow.

Drona could kill him now. Or not. There is a privacy in being the greatest warrior in the world: no one knows your limits. Drona need only kill someone else, somewhere else: any of the chariots dealing death over the battlefield, any of the elephants or tank divisions. His masters might say: “You should have killed Arjuna.” But his masters are not him, and when he strokes his mustache and says, “There were better targets,” who will know if he lies?

Drona himself would know.

He scans the battlefield for an alternative, and tries not to think about the boy he’s leaving to die.

Arjuna changes target.

Curious, Drona follows Arjuna’s new line of aim, adjusts for wind and the chariot’s speed, and sees, sword drawn on a broad broken field, surrounded by corpses of Pandava warriors, his own son. Ashwatthama, strong and tall. Ashwatthama, with his mother’s hair. Ashwatthama, whose sword runs red with blood, Ashwatthama, who has never stepped back from a fight, Ashwatthama, who can stun an elephant with a slap, Ashwatthama, who will die if Arjuna decides to kill him. Drona’s son has trained since youth, but Arjuna is a god’s child, and Drona’s finest pupil.

Arjuna prepares to loose. Ashwatthama does not know he should prepare to die.

Drona does not scream. He does not call out. Ashwatthama is miles away, and could not hear him if he did.

Drona aims for the chariot, for Arjuna, for Arjuna’s eye, for the root of his optic nerve. The arrow will enter the young man’s brain and bounce within his skull, destroying that fine killer’s mind Drona wasted years training.

Arjuna adjusts for wind, and his jaw clenches as it always does before he lets fly. A bad habit, Drona’s told him.

Drona’s arrow springs free of the bow, and hungry. It shines as it flies. If you stood before Drona and looked into his eye you would see a mandala turning, in three dimensions, a palace, a universe in which God lies dreaming of this war.

God is kind, Drona thinks, and cruel.

Arjuna’s chariot turns faster than such chariots can turn. Light twists around it, and space. In his ear, Drona hears laughter and the tinkling of bells.

The arrow strikes the chariot’s undercarriage, splinters its diamond armor, shatters its engines, slags its titanium shell. The carriage falls. Drona reaches out with his soul. He feels many spirits rise to the world above, but none of these belongs to Arjuna. Surely he would burn in death as in life, a beacon among hungry ghosts.

A god has saved Arjuna. But his carriage is broken, and he will fight no more today.

Ashwatthama is safe.

And Drona will not be forced to lie.

He smiles, and knows his smile sick. This thing he does is not glorious. That he saved his son without killing his student is an accident, no more, and it is strange to be glad of such an accidental pause from death.

Drona is no philosopher. His world is bound by duty, and by the range of his bow.

On the battlefield, the stumbling boy escapes into the wood, and is lost.

Drona strides forward on air, draws his bow, and kills again.

War does not stop at day’s end, but changes. Scouts and sentries play their games of seek and find, with knives in place of flags. Sages ride the minds of birds to plot the next day’s raids. Holy men bless certain battlegrounds to hide their soldiers’ footsteps, or blunt the enemy’s weapons. Fighting continues by other means.

The Pandava brothers and their advisors gather in the command tent. Two weeks ago, they prepared for this nightly meeting: they arrived shorn and bathed, hair and skin oiled, clad in fine silks and silver ornament, as befit their rank. Time has passed, and war has crept into their minds. Tonight they wear stark uniforms the colors of dust. Stubble grows on their cheeks and chins. They stink of fire, blood, and sweat.

Still, Yudhisthira the eldest pours them tea. He is the wisest of men, and has never lied. When he walks, his feet do not touch the ground.

Arjuna paces the tent. Since he learned to crawl he never could stay still. Like the storm his father, his life is movement. “Drona would have killed me.”

“You sound,” says Bhima his brother, “as if you are surprised.” Bhima sits like a mountain. Ten days ago he began carrying his great mace with him into the council tent. They all bear their weapons with them now. Yudhisthira has seen that mace break open the earth’s crust, until lava flowed from the wound.

Yudhisthira thinks he may be scared of his brothers.

“We are at war,” Bhima says. “Drona is the finest fighter on the King’s side. Of course he will try to kill us. I am surprised he has not already.”

“He shot at me.” Arjuna steps on the seat of his chair, steps down, turns away, circles the table. “Without warning.”

“How do you know it was him?”

“Would you like to see the chariot? I would show it to you, but I can’t, because the entire thing melted before it hit the ground.”

“He is our teacher,” Yudhisthira says, and Bhima closes his mouth. “He is our teacher, and he is a servant of our enemy. He has not tried to kill us yet because he loves us. He tried to kill you today because he can no longer make excuses for not doing so. The war does not go well for his master the King.”

“It does not go well for us,” says Dhristadyumna, their nephew. The men who cannot fly, who cannot call upon the gods for aid, who know no dharma weapons, no mantras, no deep magics, are under his command. “Four hundred thousand dead today. At least a third of those I lay at your teacher’s feet. More, if we count those he allowed his side to kill by suppressing our air support and artillery. He did not kill Arjuna, but he is slaughtering our men.”

Arjuna and Bhima do not speak. Nakula and Sahadeva, their two youngest brothers, nod. Yudhisthira bows his head, and blows on his tea. Arjuna completes his circuit of the tent, sits in his chair, stands, turns the chair around, sits again. Yudhithira paces. Air cushions his feet. Warm wind blows over and through the dead jungle outside. “Nothing will grow here again,” Yudhisthira says, and because he says it, the others know it is the truth. “I have never seen a weapon like the one Drona used on us today. His arrows consumed the world where they fell, and they traveled faster than sunlight. Arjuna, have you ever seen the like?”

Arjuna tilts his chair forward so its back rests on the table’s lip. “Drona told me once of a weapon used by God to right the world when it goes astray. No man can call upon it more than once and live. If Drona knew the secret, he never taught me. But I could feel his arrow’s strength when it consumed my chariot. If such a weapon exists, he turns it against us now.”

“Could any power resist this weapon?”

Arjuna stops drumming his fingers on the table. He sits as still as Bhima. He shakes his head.

“With all respect, my princes, you are asking the wrong questions.” The voice is new. No one turns to look. They know the speaker, though he stands in shadow. He watches them all, calm, patient, smiling. Bells ring behind and beneath his voice. Krishna is dark and lustrous, as if a glacier-melt ocean rolls within him. Naked from the waist up, slender, a blade made man. Arjuna’s charioteer. A prince in his own right. Not to mention a god.

Arjuna asked Krishna once, before the fighting started, whether it was right to kill friends, brothers, teachers in battle. Their conversation lasted fifteen minutes. Arjuna has not yet told anyone what they said, but when they finished, Arjuna blew his conch and the war began.

Once, when they all were young together, Krishna split himself into a hundred Krishnas to sleep with one hundred cowgirls. In those days, Yudhisthira thought he knew his friend. Since the war began, Yudhisthira has begun to doubt himself.

Yudhisthira turns to Krishna. “What questions should we ask?” No titles between them. They have moved beyond titles.

“You ask what is this weapon. You ask how to guard against it. You should ask: how to kill the man who wields it.” Krishna raises his hand. The fingers are long, and slender, the palm paler than the rest of him. “An armored chariot, drawn by an armored steed: difficult to overcome. But kill the driver, and what does the chariot matter?”

Arjuna lets the rear two legs of his chair fall back; they collide heavily with the floor. In the silence that follows, he stands, stretches his arms behind his head. The joints of his shoulders pop like breaking trees. “The weapon matters, because the man holds it. And while he holds such a weapon, he is invincible. Even without that weapon, I doubt any of us could best him in battle. He was our trainer. He made us. He knows how to break us.”

“The man holds the weapon,” Krishna says, “but the man is not the weapon. Convince him to set that weapon down. Then kill him.”

“He is the finest warrior in the world,” Yudhisthira says. “He will not set his weapon down just because we ask him to do so.”

“He will,” Krishna replies. “If we ask him correctly.”

“If we have a chance,” Dhristadyumna says, “we must take it. Drona has not killed any of you yet, but he is not so forgiving with our men. We cannot fight a war without them.”

Krishna smiles, and somewhere bells ring.

At dawn Yudhisthira meets the elephant. Bhima guides him; Arjuna is elsewhere, darting among the enemy ranks, slaying from above, from below, descending every so often from his chariot to kill by blade, by missile, by bow, by hand. He knows a hundred thousand ways to kill. They all do. They were well taught.

The elephant stands huge and grey and armored in the dark. His long trunk trails in the dust, and his eyes are the size of Yudhisthira’s two fists together. One jewel-tipped tusk rubs against Bhima’s armor, and Bhima laughs, and pats the creature on the forehead.

“A good soldier,” Bhima says. Yudhisthira does not expect it to be more than a good elephant. It smells of musk and earth: new to the lines, it does not yet stink of war. In the distance, the first bombs explode, and the creature pulls away from Bhima. Yudhisthira knows that elephants feel fear. “I call him Ashwatthama.” The beast calms. Its trunk twines around Bhima’s shoulders like a stole, and he hugs the trunk against his neck. He smiles, wickedly.

Yudhisthira does not smile. Yudhisthira gets the joke, and does not find it funny.

Dawn turns to morning, morning to noon. Clouds obscure the battle: dust and smoke, poison gas, magic fog. The fog does not block Drona’s sight, or his arrows. He shines on the mountaintop, a man become a god.

Ashwatthama the soldier, Drona’s son, stands in the thick of the fighting. His advance on this Pandava position, near a stand of dead jungle, has met greater resistance than the place’s limited strategic import would suggest. He has stumbled onto some secret: a cache of supplies, a hidden weapon. Ashwatthama cannot see through the dead trees. The foliage and smoke are too thick. He will press on, and investigate for himself.

Ashwatthama flows through the Pandava soldiers like a flood. His own men follow him, finishing the fallen, guarding his sides and back, but he is the leader of the wedge, and the enemy fears his flashing sword.

Ashwatthama fears, too. He lacks royal blood. He is a great warrior but he is not his father’s equal. In this sixteen days’ war he has gained respect as a fighter who does not fear pain or death, but his exploits have not earned him fame. Men still call him Ashwatthama, Drona’s son.

Ashwatthama is the son of his father, but he is more, too, and he wishes it known.

With a slash he dispatches a giant, eight feet tall with a monkey’s tail, one of the many monsters in each side’s employ. The remaining Pandava soldiers here are men, and they fall back. Ashwatthama catches one beneath the helmet strap and blood unfurls from his throat down his shining armor carapace. Another, turning to flee, is pierced where his armor joins beneath the arm, and falls. The rest retreat toward the stand of trees, and Ashwatthama pursues.

They hold these trees, this forest, important. A prophecy perhaps, that if they hold this hill they will win the war? But there are many prophecies, of victory and defeat, on each side. A weapon, hidden within? Ashwatthama cannot feel the sacred light of any divine power here, but there are ways to conceal the greatest of weapons until it is used.

Movement at the forest’s edge. Ashwatthama recognizes the shape, a man made to a bigger mold than other men, terror of the wrestling field, strongest man alive: Bhima, receding into the bushes. Bhima bears his mace, and smiles. His face is streaked with blood.

Bhima is the strongest of the Pandavas, but he is not their greatest fighter or strategist. Bhima follows the plans of his brothers. When they were children together, Ashwatthama remembers, Bhima would be the last to join any game, watching instead from the sidelines and talking softly to himself as he determined the rules. Only once he understood would he wade into play, sweeping all before him. This attitude is a product of his strength, Ashwatthama thinks. The strongest men stand still, afraid they will break the world by moving.

Bhima would not have come on his own. The others have sent him to some purpose. Ashwatthama will find out what.

Bhima is strong, but Ashwatthama is fierce, and his father has taught him secret skills. If he bests Bhima on the field of battle, the army will sing his name until the end of the world, which may not be far distant.

Ashwatthama leaps, and in spite of his forty pounds of armor he clears ten feet over the Pandava line, and lands light as a cat, sprinting forward. The dead forest embraces him. Branches and leaves ripple when he passes, like the surface of a still pool when a stone’s cast in. Then he is gone.

Drona looses an arrow with God’s power wrapped up inside it, and breaks a cliff face to rubble. An avalanche tumbles down, boulders, dirt, and chips of stone. A column of Pandava cavalry disappears in the collapse, and the falling rocks close a narrow pass through which, he expects, Yudhisthira had hoped to send a pincer movement to strike the left flank of the King’s three-pronged advance. Yudhisthira may be the wisest of men, but Drona is the master of war.

Contentment blooms inside him, as dust blooms from rubble.

Then he hears the cry: “Ashwatthama is dead!”

The dust settles.

Beneath, the war rolls on, flattening the world. Swords meet, and spears. Chariots roar, fire burns, missiles explode, elephants trumpet and warriors blow melodies of advance and retreat on conch shell trumpets. This noise he knows. Over all this a silence hangs, and Drona hears the silence for the first time now, large as the sky, vaster than ever he thought, stretching out to the stars which are not tiny dots of light but great things far away. In this silence, the cry repeats. “Ashwatthama is dead!”

He recognizes the voice.

Bhima.

Drona sweeps the battlefield from right to left and back again, and on his second sweep finds Bhima: stumbling out of a dense copse of trees, spattered in blood, carrying a bloody tunic. Ashwatthama always wore the uniform of his men. The uniform is correct. The blood looks like blood, but Drona does not expect his son’s blood to appear any different from the blood of other men. “Ashwatthama is dead!” That same-colored blood covers Bhima’s hands and face. Tears seep from his eyes and leave clear tracks in gore. His shoulders shake, an earthquake. He sinks to his knees. One of the King’s men sees a chance, runs at Bhima, and Bhima, artless, strikes him in the stomach with a flailing arm and breaks his spine. He sobs, and Drona remembers how Ashwatthama and Bhima wrestled one another as children. “Ashwatthama is dead!”

No other sound can touch the silence, so the words echo there.

Bhima cries. He should have taken Ashwatthama captive. That was his right, and Ashwatthama should have accepted captivity. But they strove always against one another. And Bhima does not know his own strength. And Ashwatthama does not know when to quit, or how.

He wants to make his father proud.

Still the words resound.

Drona cannot see within the copse. The trees are too dense; they have not yet been destroyed. Drona could loose an arrow to burn them from this distance, or break them to splinters, but if his son remains within, or his body…

No.

Bhima grieves, Bhima weeps. But Bhima may lie. Arjuna fights on foot, pressed on all sides, glowing with battle: he moves so fast his armor shines white with the heat of it. He would tell Drona the truth, but would also kill Drona if he approached now. Since the first days of the war, Arjuna has shown little hesitation. He is a good soldier.

Yudhisthira will know. And Yudhisthira will not lie. Yudhisthira is the best of men.

Drona seeks the Pandava command tent. Those three are fake. That fourth is in fact a trap set too close to the lines, inviting an assault that would overextend a hungry commander. There. The fifth tent, neither so far back from the line nor so close as to seem foolhardy, its flags present but not ostentatious, bristling with prayer antennas.

Drona’s bow is in his hand, and righteous fire fills him. He steps forward and the world flexes, kneels. Distance is one, a shadow of the mind. He enters the battlefield like a chess player’s hand enters the board, and stands before the Pandava tent. Men and monsters rush to meet him, but he still holds his bow, and the wheels of God turn about him. He stands within a diamond palace. His assailants quail and fall back.

He steps into the tent, into the shadows.

He expected more within. Screens reflect the light his body sheds. Chairs stand empty. Thick rugs’ thread glints gold. Drona wonders if he has been tricked. But no. Yudthisthira is here, and that is all Drona needs.

Yudhisthira is the son of the Lord of Judgment and a mortal woman. He is wise, and good, and he was never Drona’s favorite student, because there is a limit to how wise and good a man can be in war. And because of his slight sad smile, everpresent, which Drona felt, even when he was a man and Yudhithira a boy, boasted of knowledge he, Drona, would never attain. Yudhisthira has never lied. Drona would believe this of no other man, but Yudhisthira is barely a man: less, and at once more. His feet do not even touch the ground.

Drona steps forward and the light that moves with him, the light of his weapon, casts changing shadows on communications equipment, on maps and charts, on the planes of Yudhisthira’s face. Yudhisthira is not smiling.

“Is my son dead?”

Yudhisthira opens his mouth, but no sound comes out.

Drona realizes he could kill the Pandava with a thought. End the war here. He could have done this at any time, saved lives and stopped slaughter. The thought seems unimportant to him now, distant. But he could have saved—

“Is Ashwatthama dead?” he repeats, and realizes he is sobbing.

Yudhisthira’s throat tightens. “Ashwatthama is dead,” he says, and says something more, but the bellow of a nearby conch trumpet fills Drona’s ears and he falls to his knees and closes his eyes and feels the tears flow.

Souls depart the battlefield, hundreds at a time. They rise to the sky, and rising their color fades, their forms fail and they merge back with light, with God, and emerge again. But some, rising, endure. Their wills gird them in form and heavenly flesh, and shining with the glow of liberated spirit they approach heaven, and walk with gods. Ashwatthama was brave. Ashwatthama knew the secrets of the world. He would walk in heaven wearing his own skin. Drona too knows the secrets of the world, and rises to seek his son. His hands slack, and his bow falls from them. His skin ceases to glow. His fingers float by reflex into a mudra. Drona’s soul flies upward, living, and the gates of heaven open for him.

Ashwatthama hears the cries of his own death, but he cannot tell from what direction they come. The trees here are thick. He strikes one with his sword and it topples, but still he cannot see the sky. The copse is not copse at all but forest, and chasing Bhima he has wandered into its depths. All paths lead in, a spiral with no outer edge. He sprints, he doubles back, he seeks his own tracks and finds none. The marshy ground holds no footprints.

He smells blood, though, and thinking blood must be the battlefield he bears toward the stench. Through the pressing bushes, the thorns that catch in his hair and tear his skin, through the branches every one of which resembles an upraised mace, to the clearing at the forest’s heart. An elephant in Pandava armor lies there, bathed in a spreading pool of its own blood. Flies have found it already, and dart above staring eyes. A mace has caved in the elephant’s skull. A bloody handprint rests on one jeweled tusk, a final pat from its murderer.

Ashwatthama has seen dead animals before, has killed many. But he staggers back, and stumbles into the wood, and does not know why he is afraid.

Yudhisthira looks down on his enemy, his teacher, his friend. Divine power set aside, soul wandering heaven, Drona seems smaller even than other men, and Yudhisthira realizes it has been ten years—more?—since last he saw Drona face to face. Yudhisthira feels an unfamiliar pain.

The tent flap opens, and two men enter: Dhristadyumna and Krishna. Both grin triumph. Krishna holds his conch shell, and Dhristadyumna’s hand rests on his sword. Yudhisthira realizes that Krishna’s was the trumpet that blew, that kept Drona from hearing the second half of his sentence: “Ashwatthama is dead, but I do not know whether it is the man or the elephant.”

Krishna sets his conch shell down on a map table. “I thought,” he says, apologetic, “that you might not be able to carry through your piece. I doubt we needed the trumpet, though, in the end. He had already fallen to his knees.”

“I told the truth,” Yudhisthira says.

“Of course you did.” Krishna places his hand on Yudhisthira’s shoulder. Yudhisthira steps back, and feels the strange new pain sharper than before, and embraces Krishna and so stands entangled with his friend, Arjuna’s charioteer, the smiling god, when Dhristadyumna draws his sword and cuts Drona’s head from his shoulders.

Yudhisthira surges forward, his friend thrown aside, and catches Dhristadyumna’s sword arm before the general can put his blade away. Drona’s head tumbles to the left and rolls, lying on its side, mouth open. Yudhisthira feels the new pain, and his old rage, and a strange warmth. “Why?” He shouts, and the walls of the tent tremble.

Dhristadyumna pulls back, or tries, but his sword arm will not move. Yudhisthira’s grip might as well be forged iron. Dhristadyumna is a brave man, but he feels fear staring into the Pandava lord’s eyes. “What did you plan to do with him, once he’d thrown down his weapons? Did you think this would end with you both alive, and friends?”

“We could have bound him. Tied him. Locked him away.” Yudhisthira’s grip tightens, and Dhristadyumna stumbles. Pain contorts his fingers. The blade falls to the bloodstained carpet.

“You’ve seen him. I’ve seen him. He would laugh at prison walls. What bonds could we tie to hold him?”

“He would not have tried to escape. He is a man of honor.”

Yudhisthira could close his hand and shatter Dhristadyumna’s wrist. The general spits his words through clenched teeth. “He was a butcher. He was a force of nature. And we will win this war because he is dead.”

“Coward.” Yudhisthira releases the other man’s arm, and stumbles back. “Coward.”

“You knew this would happen,” Dhristadyumna says. “You knew. And you went ahead with it, and now you blame me.”

Yudhisthira feels the new pain again, and the new warmth.

He looks down.

He stands on the gold-thread rug, in a pool of his teacher’s blood. He stands, and the rug scrapes his feet, which have not in his many years of life ever touched the ground.

He looks up.

Dhristadyumna’s eyes are wide and dark like those of a scared animal.

Yudhisthira turns, and walks past Krishna, out the rear flap of the tent, into the light and noise and death, trailing bloody footprints.

Heaven is wheels within wheels, and each turning of every wheel a garden, a palace, a tapestry of light and choice and change. Heaven is a flower, opening.

Heaven is empty.

Drona wanders, calling, crying. “Ashwatthama! Ashwatthama, my son!”

Ashwatthama stumbles from the forest onto the broken battlefield. Above him the sky is a maze of contrails and fire. On all sides the poisoned earth stretches. Soldiers of the King and Pandavas alike clash and war, advance and retreat. Men die, and animals, and their dying looks much the same. This is the war of the world. Ashwatthama’s sword is bare, and spotted with dried blood.

He searches the horizon for his father’s light, and sees nothing.

This is the war of the world, and its heart is gone.